Edward Thorndike was an American psychologist who developed the “Law of Effect.” This is the simple idea that any behavior followed by a satisfying result is more likely to be repeated, while behaviors followed by unpleasant results are weakened. He famously discovered this by observing cats learning, through trial and error, how to escape from “puzzle boxes” to get a food reward.

Key Takeaways

- Law of Effect: Stated that behaviors followed by positive outcomes are strengthened, while those followed by negative ones are weakened.

- Experiment: Showed through puzzle boxes that cats learn to escape via gradual trial-and-error, not sudden insight.

- Theory: Proposed “connectionism,” which suggests learning is the formation of a mental bond between a stimulus and a response.

- Legacy: Provided the crucial foundation for B.F. Skinner’s later, more developed theory of operant conditioning.

- Application: Influenced education by popularizing the use of practice drills, repetition, and reinforcement in the classroom.

Law of Effect

Edward Thorndike (1874-1949) is a famous psychologist known for his foundational work on learning theory, which led directly to the development of operant conditioning within behaviorism.

The law of effect principle developed by Edward Thorndike suggested that:

“Responses that produce a satisfying effect in a particular situation become more likely to occur again in that situation, and responses that produce a discomforting effect become less likely to occur again in that situation (Gray, 2011, p. 108–109).”

This was a critical distinction in learning theory.

While classical conditioning depends on developing associations between events, Thorndike’s law established the basis for operant conditioning: learning from the consequences of our own behavior.

The Law of Effect directly explains reinforcement and punishment.

The “satisfying effect” Thorndike described is what we now call reinforcement – it strengthens the connection between a situation and an action, making you repeat it.

The “discomforting effect” is punishment – it weakens that connection, making you less likely to do it again in the future.

How did the Law of Effect influence B.F. Skinner and operant conditioning?

The Law of Effect was the direct inspiration for B.F. Skinner’s operant conditioning.

Thorndike established the core principle: consequences control behavior.

Skinner adopted this idea completely, but then he systematically studied how different types of consequences (like positive and negative reinforcement) and different schedules of delivery could precisely shape and control behavior over time.

Connectionism & Other Laws

Connectionism is Edward Thorndike’s core theory of learning.

It’s the simple idea that learning is the process of forming a mental link, or “bond,” between a stimulus and a response.

A stimulus-response bond, or S-R bond, is the mental connection you form between a specific situation (the stimulus) and the action you take in it (the response).

Thorndike believed that learning is the process of strengthening these bonds. When a bond is strong, seeing the stimulus, like a puzzle box lever, automatically triggers the correct response.

How does connectionism differ from classical conditioning?

The biggest difference is “voluntary” versus “involuntary.”

Pavlov’s classical conditioning is about involuntary reflexes, like a dog passively learning to salivate at a bell.

Thorndike’s connectionism is about voluntary, active behaviors.

The cat chose to press the lever, and the consequence of that choice – getting a reward – is what strengthened the behavior.

What are the “Law of Readiness” and “Law of Exercise”?

Thorndike’s theory explains that learning is the formation of connections between stimuli and responses. The laws of learning he proposed are the law of readiness, the law of exercise, and the law of effect.

-

Law of Readiness (motivated to learn)

- The law of readiness states that learners must be physically and mentally prepared for learning to occur. This includes not being hungry, sick, or having other physical distractions or discomfort.

- Mentally, learners should be inclined and motivated to acquire the new knowledge or skill. If they are uninterested or opposed to learning it, the law states they will not learn effectively.

- Learners also require certain baseline knowledge and competencies before being ready to learn advanced concepts. If those prerequisites are lacking, acquisition of new info will be difficult.

- Overall, the law emphasizes learners’ reception and orientation as key prerequisites to successful learning. The right mindset and adequate foundation enables efficient uptake of new material.

-

Law of Exercise (practice makes perfect)

- The law of exercise states that connections are strengthened through repetition and practice.

-

The Law of Use: This law states that the connection between a stimulus (a situation) and a response (a behavior) is strengthened when it is practiced. The more you do something, the better you get at it.

-

The Law of Disuse: This law states that the connection between a stimulus and a response is weakened when it is not practiced for a period of time. If you don’t use a skill, you start to lose it.

-

Frequent trials allow errors to be corrected and neural pathways related to the knowledge/skill to become more engrained.

- As associations are reinforced through drill and rehearsal, retrieval from long term memory also becomes more efficient.

- In sum, repeated exercise of learned material cements retention and fluency over time. Forgetting happens when such connections are not actively preserved through practice.

Puzzle Box Experiments

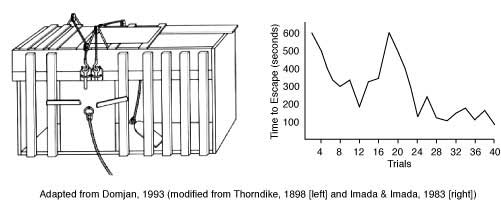

Thorndike placed a hungry cat inside a puzzle box with a bit of food outside, just out of reach.

To get the food, the cat had to accidentally perform a specific action, like pressing a lever or pulling a string, which would open the door.

He then timed how long it took the cat to escape over multiple trials to see how quickly it learned.

Results

- At first, when placed in the cages, the cats displayed unsystematic trial-and-error behaviors, trying to escape. They scratched, bit, and wandered around the cages without identifiable patterns.

- Thorndike would then put food outside the cages to act as a stimulus and reward. The cats experimented with different ways to escape the puzzle box and reach the fish.

- Eventually, they would stumble upon the lever which opened the cage. When it had escaped, the cat was put in again, and once more, the time it took to escape was noted.

- In successive trials, the cats would learn that pressing the lever would have favorable consequences, and they would adopt this behavior, becoming increasingly quick at pressing the lever.

- After many repetitions of being placed in the cages (around 10-12 times), the cats learned to press the button inside their cages, which opened the doors, allowing them to escape the cage and reach the food.

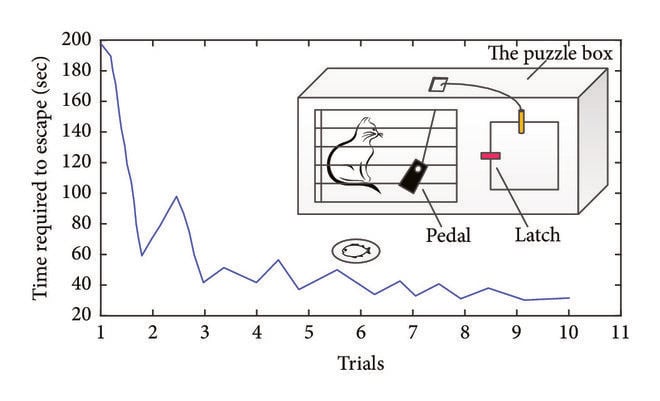

What is the learning curve in Thorndike’s experiment?

In Thorndike’s puzzle box experiments, the learning curve was a graph plotting the time it took the cat to escape (the Y-axis) against the number of trials (the X-axis).

The key finding was the shape of this curve.

The learning curve was gradual, not sudden.

-

At First: On the first few trials, the cat took a very long time to escape. It performed many random, useless behaviors (scratching, meowing, biting) until it accidentally hit the lever or pulled the loop.

-

Over Time: With each successive trial, the time it took the cat to escape decreased, but only by small, incremental amounts.

-

The Result: The graph showed a jagged but steady downward slope, which eventually flattened out as the cat mastered the task and would press the lever almost immediately.

What did the puzzle box experiments prove about animal learning?

The experiments proved that animals, in this case, cats, don’t learn through sudden moments of “insight” or human-like reasoning.

Instead, they learn by gradually connecting a specific action with a rewarding outcome.

Over time, the accidental, successful behaviors became more frequent, while the useless ones, like scratching at the bars, faded away.

Why was the “trial-and-error” finding so important?

This finding was so important because it provided the first scientific evidence for a new type of learning, which he called “trial-and-error.”

It showed that learning is a gradual process of stamping in successful responses and stamping out unsuccessful ones.

This simple, mechanical process, not high-level thinking, was the key to forming new habits.

Critical Evaluation

Strengths

Thorndike (1905) introduced the concept of reinforcement and was the first to apply psychological principles to the area of learning.

His research led to many theories and laws of learning, such as operant conditioning. Skinner (1938), like Thorndike, put animals in boxes and observed them to see what they were able to learn.

Thorndike’s theory has implications for teaching such as preparing students mentally, using drills and repetition, providing feedback and rewards, and structuring material from simple to complex.

B.F. Skinner built upon Thorndike’s principles to develop his theory of operant conditioning.

Skinner’s work involved the systematic study of how the consequences of a behavior influence its frequency in the future. He introduced the concepts of reinforcement (both positive and negative) and punishment to describe how consequences can modify behavior.

The learning theories of Thorndike and Pavlov were later synthesized by Hull (1935). Thorndike’s research drove comparative psychology for fifty years, and influenced countless psychologists over that period of time, and even still today.

1. Why did Thorndike decide repetition alone is not enough?

Thorndike also significantly revised his Law of Exercise. His original law stated that mere repetition (Law of Use) would strengthen a connection.

However, his later work showed this was incorrect. He found that repetition without feedback or reward had almost no effect on learning.

The Original Theory: “Practice Makes Perfect”

Thorndike’s original Law of Exercise (pre-1930) had two parts:

-

The Law of Use: Repeating a response in a situation strengthens the connection between them.

-

The Law of Disuse: Not using a response weakens that connection (i.e., you forget).

This was the classic “drill and practice” model. He believed, like his puzzle-box experiments suggested, that sheer repetition “stamped in” the correct habit.

The Revision: “Practice with Reward Makes Perfect”

When Thorndike ran new experiments on human learning, he discovered his original law was wrong.

In one famous experiment, he had subjects draw a 4-inch line with their eyes closed, over and over again—thousands of times.

-

The Setup: The subjects repeated the action (practice), but they were given no feedback on whether they were close to 4 inches or not (no reward/satisfaction).

-

The Result: After all those trials, their accuracy did not improve at all.

-

They were just as bad at drawing the 4-inch line on the 3,000th attempt as they were on the first.

This experiment demonstrated that mere repetition (Law of Use) is useless for learning. Practicing the wrong thing, or practicing without knowing you’re doing it right, has no effect.

The New Conclusion

Thorndike concluded that the Law of Effect (the law of reward) was far more important than the Law of Exercise.

He essentially discarded the Law of Exercise as a primary law of learning.

He revised his stance to say that repetition is only effective because it gives the Law of Effect more opportunities to operate.

-

Old Idea: Repetition + Repetition + Repetition = Learning

-

New Idea: Repetition (with reward) + Repetition (with reward) + Repetition (with reward) = Learning

In short, practice doesn’t make perfect.

Only perfect practice—where you are rewarded or at least know you are performing correctly (which is its own reward) – leads to learning.

2. What are the main arguments against Thorndike’s theories?

The main arguments against Thorndike are that his theories are far too simplistic to explain real-world human learning.

Critics, especially from the cognitive and Gestalt psychology schools, argue that he completely ignores the most important parts of learning: thinking, understanding, and insight.

His theory treats the learner as a passive “black box,” where a stimulus goes in and a response comes out, with the connection just being “stamped in” by a reward.

This fails to explain how someone understands a concept. Furthermore, Thorndike himself had to revise his own laws.

He later admitted that practice without feedback – his “Law of Exercise” – is mostly useless, and that punishment is not a simple mirror image of reward and is far less effective at changing behavior

3. Why do some critics say his theory is too mechanistic?

This is the single biggest criticism. “Mechanistic” means his theory reduces learners to simple machines, like an animal or a robot, who just react to the environment.

In Thorndike’s model, learning isn’t a process of thinking or understanding; it’s just the automatic, mechanical “stamping in” of a habit—or S-R bond—because a reward followed.

It’s a very passive process.

Gestalt psychologists, like Wolfgang Köhler, directly attacked this. Köhler’s experiments with chimpanzees showed that they could solve a problem all at once in a flash of “insight,” not just by gradual trial-and-error.

This suggests a complex, internal cognitive process—a “mental map”—which Thorndike’s mechanistic model completely ignores.

4. Does his animal-based research apply to complex human learning?

Critics argue that his animal research does not apply well to complex human learning, and here’s why:

A hungry cat in a puzzle box is learning a simple, physical, trial-and-error task to get a basic survival reward, which is food.

This is a very poor model for how a human learns something abstract, like physics, history, or philosophy.

Human learning is driven by language, social motivation, and intrinsic curiosity—not just external rewards.

For example, Thorndike’s theory can explain how a student memorizes a multiplication table using drills, but it completely fails to explain how that student understands the concept of multiplication itself or how they can creatively apply that concept to a totally new problem.

Application to Students’ Learning

Thorndike’s theory, when applied to student learning, emphasizes several key factors – the role of the environment, breaking tasks into detail parts, the importance of student responses, building stimulus-response connections, utilizing prior knowledge, repetition through drills and exercises, and giving rewards/praise.

How are Thorndike’s learning theories applied in classrooms today?

You see Thorndike’s theories everywhere in modern classrooms, especially in how we structure lessons and manage behaviour.

His Law of Effect is the simple idea of rewards, which we use in the form of verbal praise, good grades, sticker charts, or “token economies” where students earn points for participation.

His Law of Exercise, the “practice makes perfect” rule, is the foundation for giving homework, drilling multiplication tables, or using educational software that has students repeat a skill until they achieve mastery.

Finally, his core idea of connectionism is why teachers break down complex subjects into smaller, sequential steps, ensuring a student masters one concept before moving to the next

What are the benefits of using drills and repetition in learning?

The main benefit of drills and repetition, which Thorndike called the “Law of Exercise,” is to achieve automaticity.

When you practice a foundational skill, like basic maths facts or spelling, you strengthen that stimulus-response bond so much that it becomes effortless and automatic.

This is a massive cognitive benefit. It dramatically reduces a student’s cognitive load, which means their working memory is freed up.

Instead of wasting mental energy trying to remember “what’s 7 times 8?”, they can dedicate all their brainpower to solving the more complex, multi-step problem that uses that fact.

Why is providing immediate feedback and rewards important, according to this theory?

Immediate feedback is the most critical part of Thorndike’s Law of Effect because it’s all about timing.

The “satisfying” feeling of a reward—like praise or a correct answer on a screen—must happen immediately after the correct response.

This immediacy is the “glue” that fuses that specific action to that specific stimulus.

If the feedback is delayed, the student might not remember exactly what they did to get the right answer, or worse, their brain might accidentally associate the reward with a different, unrelated behavior they performed in the meantime.

Immediacy ensures you are strengthening the correct bond.

References

Gray, P. (2011). Psychology (6th ed.) New York: Worth Publishers.

Hull, C. L. (1935). The conflicting psychologies of learning—a way out. Psychological Review, 42(6), 491.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-Century.

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 2(4), i-109.

Thorndike, E. L. (1905). The elements of psychology. New York: A. G. Seiler.